How Venezuela's oil sector changed in 2024

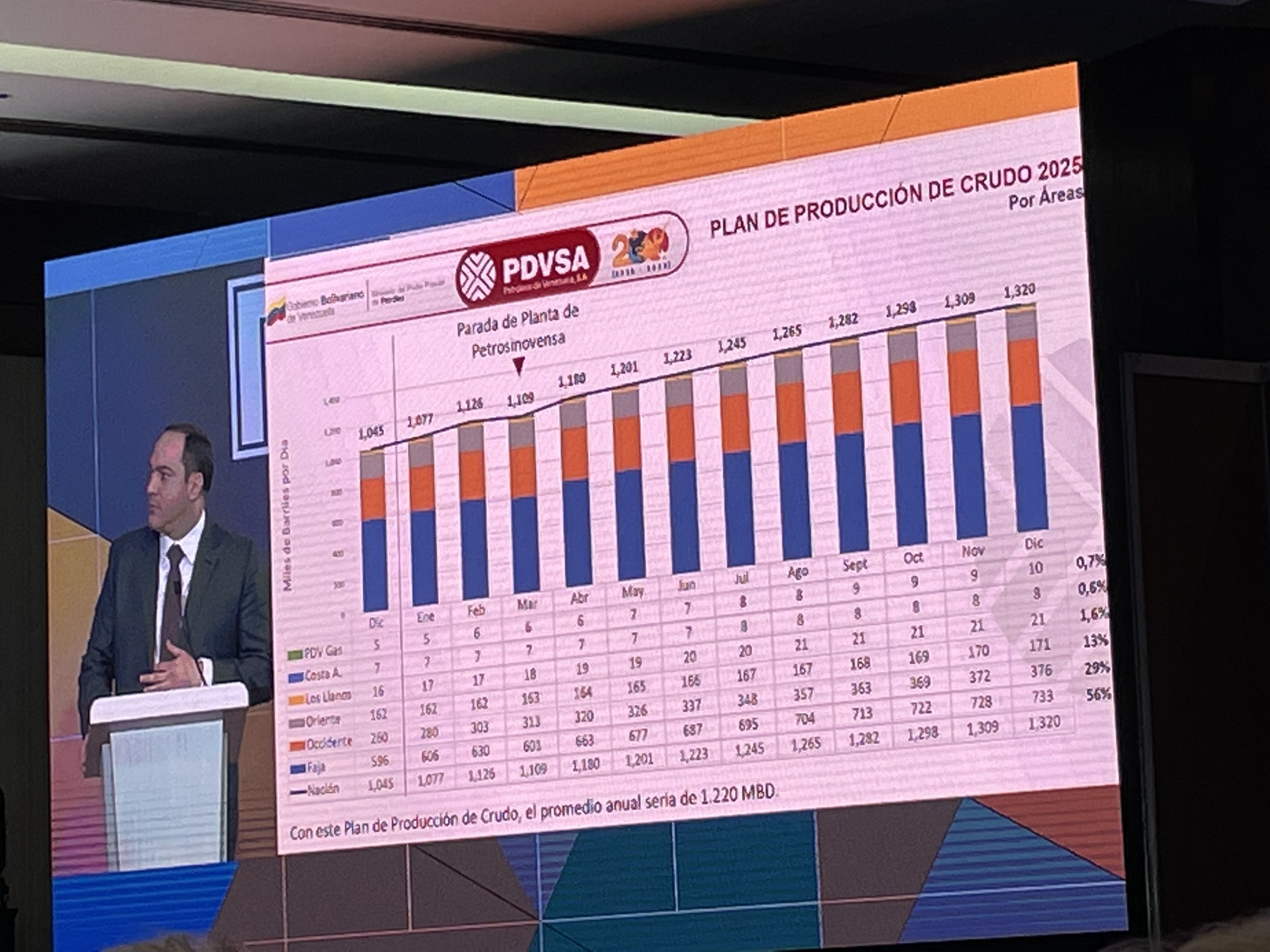

PDVSA president Hector Obregon presents the 2025 production targets for Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, to the Camara Pertolera at its annual event on 20 November 2024. Elias Ferrer.

The year 2024 was a rocky one for Venezuela’s oil sector. Production, investment, and exports grew, yet facing many challenges and uncertainty.

January started with General License 44 in force, which made an exception to U.S. sanctions on PDVSA for six months. In April, the Biden administration allowed it to expire, citing the ban on opposition leader Maria Corina Machado.

Since, the Biden administration introduced a 45-day “wind-down period,” and then granted specific licenses to companies already operating in Venezuela. One of the reasons was to allow such corporations to recover investments and large debts owed to them by PDVSA.

In July, Venezuelans went to vote in a polarised election with a contested outcome. Both the government and the opposition claimed victory, while the electoral authority did not publish disaggregated results, as it is required by law. Many foreign states refused to recognise incumbent Nicolás Maduro’s victory, and Venezuela’s oil sector gained another layer of uncertainty.

In August, oil minister and PDVSA president Pedro Rafael Tellechea was replaced by Vice President Delcy Rodriguez and Hector Obregon for each post. He was soon after imprisoned, on charges of selling sensitive information to U.S. intelligence.

Tellechea’s original target of 1.3 million barrels per day (b/d) by the end of 2024 was far from being met, and it is now next year’s goal. Crude oil production nonetheless rose throughout 2024, with only a slump at the end of the year with fires and explosions in the Muscar Gas Complex and the Jose Petrochemical Complex.

OPEC figures show that the daily crude oil output average was 749,000 b/d in 2023, and 856,000 b/d in 2024, a 14% increase—according to secondary sources, as opposed to direct reporting by Venezuela’s Ministry of Hydrocarbons.

According to the same organisation, crude oil production fell by 25,000 b/d in November, but picked up by 9,000 b/d in December. This last increase was despite lingering problems in Eastern Venezuela, being offset by rising output in the West.

Estimates can vary due to their methodology, for example, depending on whether they include or subtract imported diluents from the final output figure.

An internal PDVSA report for December shows that crude oil output grew by 34% since January. By the end of the year, joint ventures would have contributed 202,000 b/d, while PDVSA’s “own effort” operations would have produced 66,000 b/d.

There was also a marked shift in the destination of Venezuelan oil exports. There is no official data on this topic, but different firms and analysts have produced estimates based on shipping information.

Economists Asdrubal Oliveros and Juan Palacios, in the book On Sanctions in Venezuela, find that, from 2023 to 2024, exports to the U.S., Spain, and India rose at the expense of China and Malaysia—in this case, an intermediary for exports to China’s “grey market.” In 2023, the first group received 34% of Venezuelan crude exports while the second one 51.6%. In 2024, these shares were practically inverted, with 56.2% and 26.8% respectively.

Reuters also publishes monthly data on exports, looking at key destinations. Exports to Europe refer to shipments taken by Repsol, Eni, and Maurel et Prom.

Reuters data reflects the same development. Venezuela exported more oil overall, but less to ideological allies China and Cuba, with a redirection to the U.S., Europe, and India. This is despite political rhetoric, where PDVSA has stated a goal of increasing exports to Asia, with an emphasis on “China, India, and Southeast Asia.”

Deals in the sector have been mostly about smaller companies with an appetite for high risk. These have mostly drawn capital from North America and Western Europe. Meanwhile, other major players like Russia and China have held on to their assets.

A notable deal has been the creation of the joint venture Petrolera Roraima in the Orinoco Oil Belt. A&B Oil and Gas holds a 49% stake, while PDVSA the remaining 51%. The company is headed by Venezuelan businessman Jorge Silva, who has been able to draw capital from Brazil, where he has many business interests, especially in the agricultural sector.

In an official press release, the company said that Petrolera Roraima started producing 22,000 b/d, and was forecast to reach 45,000 b/d by the end of 2024.

Some joint ventures have been expanded geographically, as is the case for Repsol’s Petroquiriquire, or renewed for periods longer than usual, like Chevron’s Petroindependencia.

Joint ventures that were formerly in the hands of Rosneft have been transferred to alternative, Russian-state-owned firms, like Petromost. This company has also had two of its ventures renewed by the National Assembly this year: Boqueron and Petroperija.

British giants Shell and BP moved ahead with offshore gas projects in shared Venezuelan-Trinidadian waters, and were able to obtain licenses from the U.S. OFAC.

Also in the realm of natural gas, this past year Repsol exited the onshore Yucal Placer field, selling its minority stake to Sucre Energy, already the majority partner. Formerly in the hands of TotalEnergies, Yucal Placer is currently estimated to produce 80 million cubic feet of gas.

This year is uncertain, but the second Trump administration should soon show its intentions. Will it open up space for U.S. and allied countries to invest in and buy Venezuelan oil? Or will we see sanctions tighten up once more?

Chinese, Russian, Turkish, Algerian, and Iranian companies have shown an interest in the country’s oil reserves, but will they put their money where their mouth is? Or will they just hold on to what they already own?